Lol @ new xkcd

-

Please stop embedding files/images from Discord. Discord has anti-hotlinking logic in place that breaks links to Discord hosted files and images when linked to from anywhere outside of Discord. There are a multitude of file/image hosting sites you can use instead.

(more info here)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

-

The minor scale is one of the modes of the major scale.Lace said:What intervals compose the minor scale? Unless I missed a post or two, you only explicitly described major scales and their modes.

Wedge of Cheese said:By the Baroque period, only Ionian and Aeolian were still commonly used, and they were renamed major and minor, respectively.

Okay, so a whole note is an open circle (more of an ellipse, really, but we'll just call it a circle)Lace said:The main thing I don't understand about musical notation is the 3/4 time or 4/4 time part. Would you mind explaining that?

A half note is an open circle with a vertical line attached (called a "stem"). The duration of a half note is, logically, half that of a whole note.

A quarter note is a filled in circle with a stem, and is half the duration of a half note.

Notes shorter than quarter notes have beams or flags attached to their stems. Each flag or beam cuts the duration in half.

The fraction formed by the time signature indicates the number of whole notes in each measure. A measure is the distance between two consecutive barlines, and the barlines are the vertical lines between notes. So for example in 3/4 time, the duration of each measure is 3/4 the duration of a whole note. There are many different combinations of notes that could add up to 3/4 of a whole note (i.e. half+quarter, quarter+half, quarter+quarter+quarter, eighth+half+eighth, etc). You might be wondering why ones like 4/4 don't just get reduced to 1/1 or perhaps just 1. The reason is that the number on the bottom tells you what type of note is the basic "rhythmic unit" of the piece. So in both 3/4 and 4/4, a quarter note would be that basic unit (meaning that, if I were conducting a piece in x/4 time, I would move my hands every quarter note, and I would do so x times per measure). If you just see the letter C as the time signature, it means "common time" which is 4/4. If you see a C with a line through it, that means "cut time" which is 2/2 (same measure length as 4/4, but one would only conduct 2 beats per measure instead of 4).

Haha yes, quite awesome indeed!Lace said:I was actually, nerdy as I am, thinking of it in terms of solutions to indefinite integrals. They all hold the same pattern, but can be shifted by a constant. Awesome, right?

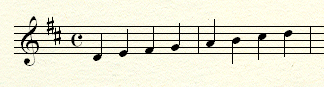

Well, first of all, F major is F, G, A, B-flat, C, D, E. Anyway though, if you wrote a piece using only the notes F, G, A, C, D, and E, and you made F the tonic, then it would be correct to say that the piece is in the key of F major. However, if you just played those 6 notes by themselves, it would not be correct to say that you had just played an F major scale.Lace said:If my scale is, say, {F G A C D E} would that still be F Major even though it doesn't have a B?Only 11 more posts (10 after this).That's a good pausing point.We're almost done with scales. Just one more thing I want to mention regarding the minor scale. You may hear people talk about the 3 different types of minor scales (natural, harmonic, and melodic). The one we've been discussing so far is the natural minor, and for now, we won't worry about the other 2. The harmonic minor has a slightly different sequence of intervals than the natural, and the melodic actually has 2 different sequences of intervals, depending on whether it's going up or down. Even if a piece uses the harmonic or melodic minor, the key signature is always derived from the natural minor (i.e. in all my life, I've never seen a piece written specifically "in the key of __ harmonic minor" or "in the key of __ melodic minor"). For now, just know that the other 2 exist.Oh, and also, on the off chance that I wanted to throw a plain F or a plain C in the piece (F natural or C natural), I could just put a natural sign in front of the notes I wanted naturaled and that overrides the key signature, like so:

When notating music, key signatures are a very handy shortcut. Strictly speaking, you don't need to know about them when making music in a medium like Organya where you don't have to notate sharps/flats, but they're still helpful to know about.

When notating music, key signatures are a very handy shortcut. Strictly speaking, you don't need to know about them when making music in a medium like Organya where you don't have to notate sharps/flats, but they're still helpful to know about.

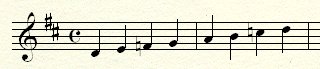

Suppose I'm writing a piece in the key of D major (recall that the notes in the D major scale are D, E, F#, G, A, B, and C#). This means that almost every note in the piece will be one of those 7 (very rarely will there be a D#/Eb, F, G#/Ab, A#/Bb, or C). I could write every F and C in the piece with a sharp in front of it, like so:

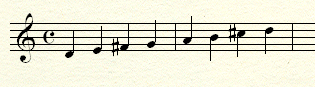

or I could put a key signature at the start of each line of music, which indicates to the performer that every F and C in the piece should be sharped, like so:

In addition to making notation easier, key signatures have the advantage of letting the performer know what key the piece is in. In this case, the performer looks at the F#/C# key signature and knows that the piece is either in D major or B minor (which has the same key signature as D major, and is called the "relative minor" of D major). Or it could be in E Dorian, F# Phrygian, G Lydian, A Mixolydian, or C# Locrian, all of which have that same key signature.From this point on, we'll be looking mostly just at major and minor scales, and only occasionally at the other 5 modes (for example, "Arctic Frolic" from TWoR happens to be in C# Dorian).

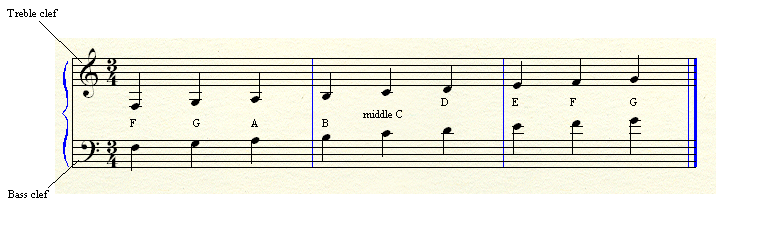

I can't remember if you said you already know how to read notes on a staff, so I'll either remind you or show you now...

2 clefs (there are others, but they're really obscure and we won't worry about them):

As you can see, going up to the next highest line or space goes up a white key, and going down to the next lowest line or space goes down a white key. If you go off the top or bottom of the clef, you can add extra lines (called "ledger lines"). Middle C is on the first ledger line above the bass clef, and the first ledger line below the treble clef. In Organya, middle C is called C3, but it's actually more standard to call it C4. Sharps and flats are added just before notes.I should also note that the Baroque, Classical, and Romantic periods are collectively called the "Common Practice" era, and most of the theory we'll cover will be the theory of that era. However, Common Practice theory is certainly not the only valid approach to music theory. It simply defines a method for composing and analyzing music, but it is not the only method. It's just the method I'm most knowledgeable about, and it's the method that yields music most "familiar" to our 21st Century American ears.Okay, so now we know that the interval sequence for a major scale is: M2, M2, m2, M2, M2, M2, m2. There are several ways you could modify this sequence. The most common is to "rotate" the sequence (i.e. take a certain number of intervals from the front of the list and move them to the back, or vice versa). There are 7 different rotations (called "modes") of the major scale, including the major scale itself. They are named as follows:

M2, M2, m2, M2, M2, M2, m2 (Ionian)

M2, m2, M2, M2, M2, m2, M2 (Dorian)

m2, M2, M2, M2, m2, M2, M2 (Phrygian)

M2, M2, M2, m2, M2, M2, m2 (Lydian)

M2, M2, m2, M2, M2, m2, M2 (Mixolydian)

M2, m2, M2, M2, m2, M2, M2 (Aeolian)

m2, M2, M2, m2, M2, M2, M2 (Locrian)

All of these, except Locrian, were commonly used during the Ancient and Medieval periods. During the Renaissance, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, and Mixolydian began falling out of favor. By the Baroque period, only Ionian and Aeolian were still commonly used, and they were renamed major and minor, respectively. The other 5 didn't start reappearing until the late 20th Century, and, even now, they aren't used nearly as much as they were in the Ancient period (with the exception of Locrian, which wasn't used at all in the Ancient period, as far as we know today). The reasons for Ionian's and Aeolian's dominance and for Locrian's exclusion are quite interesting, but they'll have to wait for when we cover chords.How do you like having double digit notifications when you log on? I think the most I've ever had at once is 6.Okayz, here we go again.Oh and thou shalt write the next chapter of the Book of Cheese or else shalt thou be forsaken by the Lord thy God.and I'mma take a breather now. Only 22 more posts (21 after this one).Before I go on, a very brief, very approximate, and very oversimplified history of Western music:

Ancient: ??? - 500 (Greeks)

Medieval: 500 - 1400 (Perotin, Machaut, Landini)

Renaissance: 1400 - 1600 (Desprez, Palestrina, Weelkes, Gesualdo, Dowland)

Baroque: 1600 - 1750 (Bach, Handel, Vivaldi, Pachelbel, Scarlatti, Purcell, Monteverdi)

Classical: 1750 - 1825 (Beethoven, Mozart, Haydn)

Romantic: 1825 - 1900 (Schumann, Schubert, Chopin, Liszt, Wagner, Brahms, Tchaikovsky)

20th Century: 1900 - 2000 (Debussy, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Copland, Bernstein, Cage)

???: 2000 - ??? (???)Now, if you're really smart, you're thinking "wait a minute, that series of intervals doesn't fully describe the C major scale; it tells me how far I have to jump from each note to the next, but it doesn't tell me what note to start on," and you would be absolutely right in thinking this. As it turns out, now that you know the series of intervals that describes the C major scale, you can figure out the notes of ANY major scale. This is because all major scales have the same series of intervals. For example, suppose you wanted to know the notes of the D major scale. You would simply start on D and follow the same series of intervals, like so:

M2 above D is E

M2 above E is F#

m2 above F# is G

M2 above G is A

M2 above A is B

M2 above B is C#

m2 above C# is D

So you get the notes D, E, F#, G, A, B, C#. Then the final intervals brings you back around from C# to D, thus completing the circle. A good way to check if you did it right is to see if you landed on the same note you started on.It can sometimes be helpful to think of a scale as a series of intervals rather than a series of notes. For example, take the C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B). Rather than thinking of this as 7 notes, you can think of it as 7 intervals (not 6 intervals; remember we're thinking circularly now, so once you get to B, you have to get back to C). The 7 intervals are:

C to D: M2

D to E: M2

E to F: m2

F to G: M2

G to A: M2

A to B: M2

B to C : m2

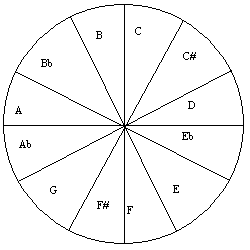

So the C major scale can be described by the series of intervals: M2, M2, m2, M2, M2, M2, m2.Now, as I said before, scales in almost all Western music function more like ordered lists than like unordered sets, so how do we know what order to put the notes in? Well, the tonic always comes first, and the notes are always in clockwise order on the chromatic circle. For example, suppose I told you that the notes of the F# dorian scale are B, D#, G#, F#, E, A, and C# and wanted you to tell me the correct order of the notes. You would start with F#, then go to the next one clockwise on the chromatic circle (G#) and then A, then B, then C#, D#, and finally E.Since scales are not octave dependent, it is helpful to think of the 12 different pitches as being arranged in a circular fashion, rather than a linear one, like so:

We'll call this the "chromatic circle".

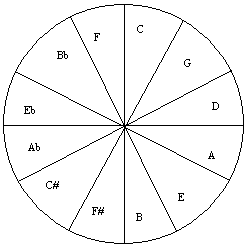

For reasons we'll see later, it can also be helpful in many situations to think of the 12 pitches in a related but different circular fashion, in which, instead of going up one half step with each clockwise move, we go up a perfect 5th, like so:

We'll call this the "circle of fifths". If you're really awesome, you may have noticed that the interval from C# to Ab is technically not a perfect 5th, but actually its enharmonic equivalent: a diminished 6th. This doesn't really mean anything special, but it is necessary to make one of the 12 intervals a d6 instead of a P5 in order to make the circle work (i.e. to finish on the same note you started on).At this point, our notion of thinking of a scale as a "set" of notes (in the mathematical sense) sort of breaks down, since, in Western music, scales almost always have a "tonic", which is basically the central note in the scale. This means that scales are no longer unordered sets but ordered lists. It also means I'm going to stop putting curly braces around the scales (plus they're just starting to get annoying to type). You can tell which note in the scale is the tonic just by looking at its name (i.e. the tonic of C major is C, the tonic of F minor is F, etc). -

Loading…

-

Loading…

-

Loading…

-

Loading…